Kavya Wadhwa

Nuclear Energy, Technology, Security & Policy

The Einstein Myth: How E=mc² Didn’t Build the Atomic Bomb

If E=mc² truly explained the atomic bomb, then why does a kilogram of uranium-235 release a million times more energy than a kilogram of TNT? Both obey the same equation, both convert mass to energy with the same factor c². The answer lies not in Einstein’s relativity, but in the binding forces that hold atomic nuclei together.

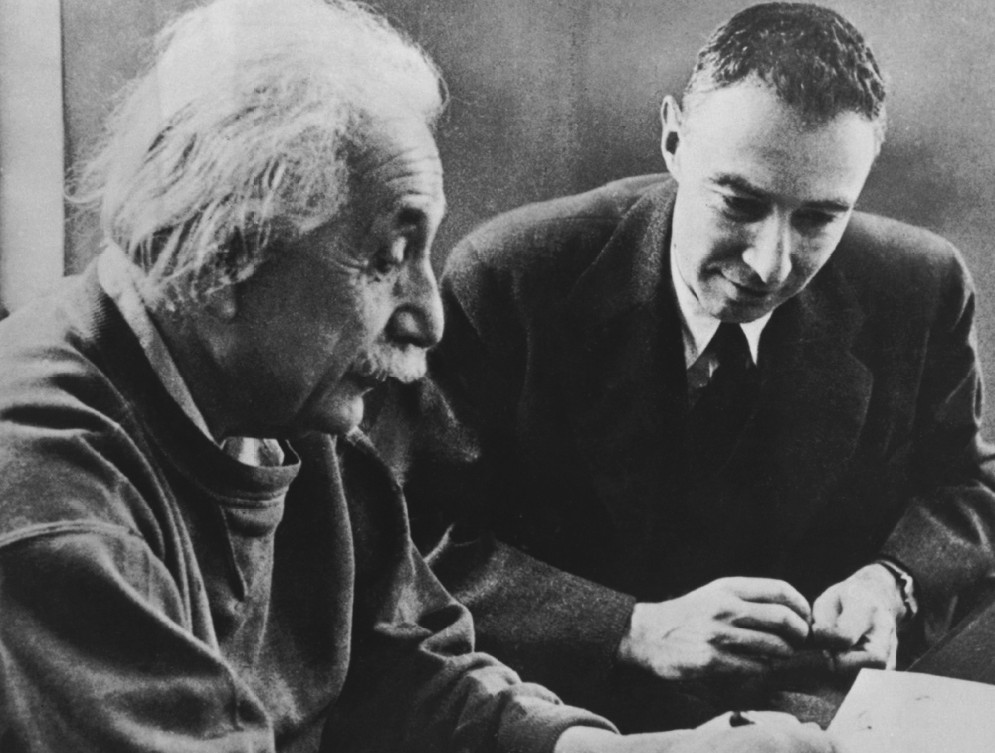

In the collective imagination, Albert Einstein and the atomic bomb are inseparably linked. After Hiroshima and Nagasaki reduced two Japanese cities to radioactive rubble in August 1945, TIME magazine crowned Einstein the “father of the bomb,” crediting his famous equation with making nuclear weapons theoretically possible. The equation E=mc² became synonymous with apocalyptic power, cementing its place as perhaps the most recognized scientific formula in history.

There’s just one problem: this story is largely a myth.

The uncomfortable truth is that Einstein’s most famous equation played virtually no role in the development of nuclear weapons. The atomic bomb would have been built with or without Einstein’s 1905 paper on mass-energy equivalence. Understanding why requires digging into what the Manhattan Project actually needed and what it didn’t.

What E=mc² Actually Says

Before dismantling the myth, it’s worth understanding what Einstein’s equation really means. In essence, E=mc² states that mass and energy are interchangeable: two forms of the same fundamental quantity. The “c²” (the speed of light squared) is simply a conversion factor, telling us how much energy corresponds to a given amount of mass.

This applies universally. When you burn wood, the ash and gases produced weigh slightly less than the original wood and oxygen that combined. That missing mass became energy: the heat and light of the fire. The same principle applies when gasoline combusts in your car’s engine or when your body metabolizes food.

Nuclear reactions follow the same rule, just with far more dramatic results. The difference isn’t that nuclear reactions obey E=mc² while chemical reactions don’t. Both do. The difference lies in how tightly atomic nuclei are bound together compared to how chemical bonds hold molecules together.

What Actually Makes an Atomic Bomb Work

The atomic bomb doesn’t work because of E=mc². It works because of the specific properties of certain heavy atomic nuclei and the nature of nuclear forces.

Here’s the real story: When a uranium-235 nucleus absorbs a neutron, it becomes unstable and splits into two smaller fragments. These fragments weigh slightly less in total than the original uranium nucleus. The missing mass has been converted to kinetic energy. The fragments fly apart at tremendous speeds. More importantly, this fission also releases additional neutrons.

Those newly released neutrons can then strike other uranium-235 nuclei, causing them to split and release more neutrons. If you have enough uranium-235 packed closely enough together (what physicists call “critical mass”), you get a runaway chain reaction. In a fraction of a second, trillions upon trillions of atoms split, releasing all that energy essentially simultaneously. That’s an atomic explosion.

Notice what’s missing from this explanation: Einstein’s equation. The Manhattan Project scientists didn’t need E=mc² to understand any of this. They needed to know about:

- Nuclear fission and how it works

- Neutron behavior in different materials

- How to calculate critical mass

- How to separate uranium-235 from the far more common uranium-238

- How to design an implosion mechanism to compress plutonium

- How to initiate a chain reaction at precisely the right moment

These were problems of nuclear physics and engineering, not relativity theory.

The Equation That Wasn’t Used

The physicist and science writer L.A. Paul has pointed out something particularly revealing: E=mc² applies equally to all reactions, chemical and nuclear alike, with the exact same conversion factor. Yet chemical explosions like TNT are millions of times less powerful than nuclear explosions per unit mass.

If E=mc² were the key to understanding the atomic bomb, it should apply just as much to conventional explosives. But it doesn’t explain the difference between them. What does explain the difference is the binding energy of atomic nuclei versus the binding energy of molecular bonds: a detail from nuclear physics, not from Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Furthermore, scientists working on the Manhattan Project could directly measure the energy released in nuclear reactions. When they observed uranium fission in laboratory experiments, they could detect and quantify the energetic particles produced. They didn’t need to calculate E=mc² to know that enormous energy was being released. They could see it and measure it.

The equation that actually mattered for bomb calculations was one describing neutron multiplication rates, not mass-energy equivalence. The practical question wasn’t “how much energy could theoretically be released?” but rather “will this configuration sustain a chain reaction long enough to produce a significant explosion before it blows itself apart?”

Einstein’s Real Contribution

This isn’t to say Einstein had no connection to the atomic bomb. His actual role, however, was political rather than scientific.

In 1939, several physicists who had fled Nazi Germany (including Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner) grew alarmed by the possibility that Germany might develop nuclear weapons. They drafted a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt warning of this danger and urging the United States to begin its own nuclear research program. Because Einstein was the most famous scientist in America, they asked him to sign it, believing his signature would command Roosevelt’s attention.

Einstein agreed, and the Einstein-Szilard letter helped catalyze what eventually became the Manhattan Project. But Einstein himself never worked on the bomb. The FBI considered him a security risk due to his pacifist political views and associations with leftist causes. He was deliberately kept out of the program.

Years later, Einstein reflected on his indirect role with evident regret. He reminded people that he did not consider himself the father of atomic energy’s release, describing his part as “quite indirect.” In his final years, he became an advocate for nuclear disarmament and international control of atomic weapons.

Why the Myth Persists

If E=mc² didn’t enable the atomic bomb, why is the connection so firmly planted in popular consciousness?

Part of the answer is timing. Einstein published his equation in 1905. Forty years later, atomic bombs destroyed two cities, seemingly validating his insight that tiny amounts of mass contained staggering amounts of energy. The symbolic connection was irresistible, even if the technical connection was tenuous.

Media coverage after Hiroshima and Nagasaki reinforced this narrative. Einstein was already the world’s most famous scientist, the embodiment of genius itself. Linking him to the war’s most fearsome weapon made for compelling storytelling. TIME’s declaration of Einstein as the bomb’s “father” crystalized an association that persists to this day.

There’s also a tendency to credit theoretical physicists with practical achievements they didn’t directly enable. We like origin stories that trace world-changing technologies back to pure insights by individual geniuses. The reality (that the atomic bomb emerged from decades of cumulative research by hundreds of scientists and engineers working on specific, practical problems) is less narratively satisfying.

What This Means for Science

The Einstein-bomb myth matters because it distorts how we understand scientific progress. It suggests that technological breakthroughs flow directly from theoretical insights in a straightforward line. In reality, the relationship between theory and application is far more complex and indirect.

E=mc² is a profound insight about the nature of reality. It reveals a deep unity between what we thought were separate phenomena. It’s important and beautiful on its own terms. But its importance doesn’t depend on whether it enabled nuclear weapons, and it didn’t.

The atomic bomb emerged from nuclear physics, not relativity theory. It required understanding the specific behavior of neutrons, the properties of uranium and plutonium isotopes, and countless engineering details about metallurgy, explosives, and electronics. The scientists and engineers who built it would have needed essentially the same knowledge even if Einstein had never published a single paper.

Perhaps there’s something fitting about this. Einstein was a pacifist who spent his later years advocating for peace. The weapon that linked his name to apocalyptic destruction didn’t actually need his most famous idea. The real Einstein (the one who questioned authority, championed international cooperation, and warned against the dangers of nationalism) deserves to be remembered for his actual contributions, not for a bomb he didn’t build with an equation that wasn’t required.

The atomic bomb stands as one of humanity’s most consequential creations, for better and worse. But we should credit or blame the right people and the right ideas. E=mc² explained what was happening when atoms split and mass became energy. But it didn’t tell anyone how to split those atoms, how to start a chain reaction, or how to build a weapon. That knowledge came from elsewhere, from different people working on different problems.

Einstein’s equation describes the universe. The atomic bomb changed it. But those are two different achievements, and it’s time we stopped conflating them.